The Circle Never Ends

2003 - Present

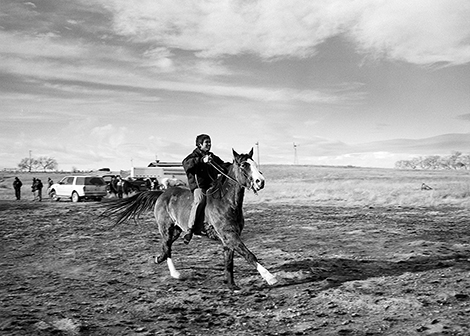

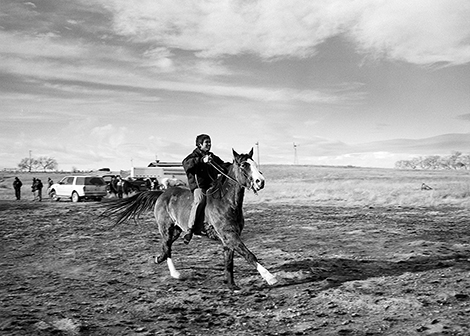

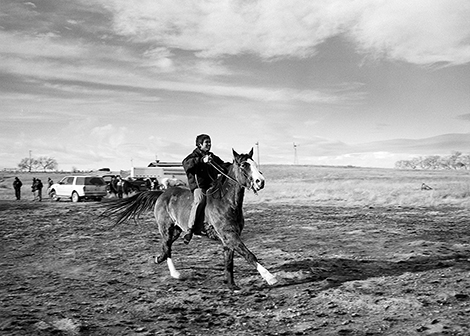

Every December, sturdy horses break into a fierce gallop across the winter plains in South Dakota, United States. While some ten riders ride across the field at first, several hundred soon follow, trailing a cloud of hot breaths on the snow-covered prairies. The surroundings boom with the clatter of hooves. By the time the group that was rushing across the snowfield a moment ago disappears beyond the distant horizon and their echo turns into silence, you start to wonder whether the reverberations that you just heard weren’t in fact communications with heaven itself.

The “Future Generation Ride” introduced in this volume is a ritual performed by Native Americans today to remember their ancestors. Begun to commemorate their forefathers, who had fought against white men in the 1800’s, and to appease their souls, it has become an official, annual event for Native Americans. Conducted on horseback, this event starts every December 15 on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota, where Native American chieftains were murdered in succession, and covers a distance of approximately 311 miles. Today, this horseback riding event serves as an opportunity for young Native Americans to find their cultural identity and for older Native Americans to raise their voices against mainstream American society and to remember their ancestors’ spirit of independence. The historical context and origins of the event are as follow.

During the final week of December 1890, Chief Big Foot, together with his people, walked down to Pine Ridge, covering a distance of 150 miles. This was because, earlier, on December 15, Sitting Bull, another great chieftain, had been shot to death by the government-affiliated Native American police. Hearing the news, Chief Big Foot felt possible threat from American government troops and therefore decided to seek refuge with Chief Red Cloud, who was on relatively good terms with the United States military. However, he and his tribesmen were arrested on December 28 at a creek near Wounded Knee by Major Samuel Whitside and his detachment of the Seventh Cavalry. The next morning, they were massacred in the same spot. By coincidence, it was also here that, 13 years before, in 1887, the great chieftain Crazy Horse had been buried.

When Chief Big Foot and his people were passing Wounded Knee, the some 500 members of the Seventh Cavalry had already surrounded the area. While the arrested Chief Big Foot and his tribesmen were spending the night in a camp, Colonel James Forsyth ordered four Hotchkiss guns to be placed around the Native Americans’ tepees. During the American soldiers’ disarmament of the Native Americans next morning, there was a gunshot after a minor skirmish between the two parties. Then the United States troops opened fire. By the time gunfire ceased, nearly all tribesmen had fallen on the snowfield. Although the American military’s pretext for the arrest and disarmament had been hidden weapons, only two guns were found among the Native Americans. Out of the 350 tribesmen, 250 were women and children, and over 300, including them, were murdered. When a snowstorm arose after the massacre, the United States troops left, abandoning the bodies of Chief Big Foot and his tribesmen. When they returned in early January 1891 for burial, the bodies were still strewn on the ground, frozen in their last moments of horror and pain. The soldiers then dug a large hole and dumped all the bodies in it. This is what has come to be known as the “Wounded Knee Massacre.”

Between winter 1968 and 1969, scores of years after the Wounded Knee Massacre, a young Native American named Birgil Kill Straight was suffering from a repeated dream. In the dream, he would be following, together with other Native Americans, the path that Chief Big Foot had trod. Upon hearing the story of this dream, the boy’s father suggested that they perform rituals to commemorate their ancestors. Thus begun, these commemorative rituals paved the way for the horse-riding event today.

However, Birgil once again had the same dream for 3 years from 1982. He finally told a medicine man of his dream, and, after discussion with those around him, decided to retrace Chief Big Foot’s path on December 22, 1986, together with seventeen other riders and starting in Bridger, Cheyenne River Indian Reservation, to appease the ancestors’ spirits. Dubbed the “Chief Big Foot Memorial Ride” and continued for 5 years, this event came to a climactic conclusion in 1990, the centennial of the Wounded Knee Massacre, with the participation of several thousand Native Americans.

From then on, this event was continued by new, young leaders. In 1988, at the suggestion of Ron His Horse Is Thunder, the leader of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, leaders of other tribes gathered to change the original route, which covered 150 miles from Bridger to Wounded Knee, so that it now covered 300 miles, encompassing Sitting Bull’s Camp on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. Paused in 1991 but resumed in 1992, this trip is called “Omaka Tokatakiya (Future Generation Ride)” in Native American society. This horseback journey continues for 2 weeks in the bitter cold of -4° F to -22° F. Because the event is held in winter, some have also dubbed it the “Winter Sun Dance.” Unlike most Americans, who spend Christmas and the New Year’s Day in comfort, Native Americans withstand this period by making a fire in cold gyms or outdoors to warm themselves.

In 2005, 14 years after the creation of the official title “Future Generation Ride,” I finally had a chance to take part in this event, which I had heard of so much. During the 2-week period, I was able to have a glimpse of Native Americans’ lives today. Even though it is in form a ritual, the event is in fact a microcosm of Native Americans’ lives, demonstrating their history, culture, and spiritual world.

When I boarded a plane to study photography in New York City in the summer of 2002, my main interest lay in the lives of Korean immigrants. Participation in the “Everyday Life in Korean History” series published by Sakyejul Publishing, Ltd. since 1999 had opened my eyes to Korean history, in turn expanding my interest to include ethnic Koreans abroad, who remembered and represented the living past.

It may have been luck. 2003, a year after my departure for studies in the United States, marked the 100th anniversary of Korean immigration to America. I became curious about the stories of these people, who had had to settle down in an unfamiliar land. At the same time, I wanted to learn about the lives of minorities who were living on the boundary of mainstream society. One thing that surprised me was that, thanks to the fruit reaped by the African-American civil rights movement, the human rights of non-white peoples including Asians in New York City had improved considerably so that there no longer were accidents due to racial discrimination.

After I met the late Mr. Sun-man Im, my interest in Korean immigrants and social minorities in the United States as well as their movements led to the history and reality of Native Americans. Having immigrated to the United States in 1953 and devoted all his life to the human rights movement, Mr. Im had originally specialized in outcast communities of the world. The Gypsies of Europe, Sudras of India, and butchers of Asia had been his main focus and interest. This encounter naturally sparked in me an interest in Native Americans, who are minorities in the United States. In 1992, when Mr. Im had been actively conducting research, the European Union had decided to celebrate the year as the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’ “discovery” of the Americas. Of course, opposed to such an idea, Native Americans had demonstrated in front of the United Nations building until the plan had been scrapped. What an irony. I will discuss this again later, but Columbus’ “discovery” of the continents spelled disaster for one race even though it may have been a blessing to another. Looking back, his “discovery” was the beginning not of cultural diversification but of cultural homogenization and assimilationism as well as the manifestation of imperialistic policy.

Watching Mr. Im work for Native Americans, I increasingly wanted to experience and to observe these peoples’ lives and problems on Indian reservations. Thanks to his help, I was finally taking the first step toward my own Native American project. And, in 2003, I had an opportunity to visit Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation as the first site of my exploration of Indian reservations. Not coincidentally, it is here that the remains of Big Foot, mentioned above, as well as Crazy Horse, yet another great Native American chieftain, rest.

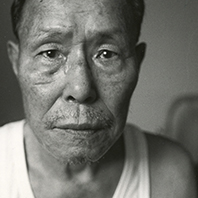

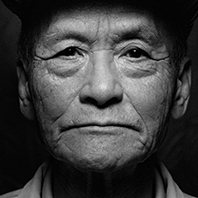

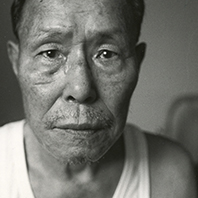

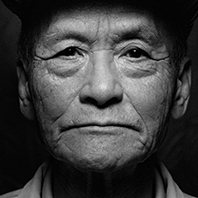

In the process of working on this project, I met countless Native Americans and got to know of their past and present lives. Some 500 nations peacefully coexisted all over the continent before Europeans’ arrival in 1492. After that fateful year, 250 nations became extinct over the next four centuries due to white men’s invasion and genocide. The survivors live on, divided and committed to 274 Indian reservations.

The most impoverished areas in the United States today are in fact the Indian reservations. Most of our misconceptions about Native Americans stem from the United States government’s policy on these peoples. Things that are prohibited by state laws are condoned on Indian reservations. Native Americans are carelessly left to fend for themselves in places where nuclear waste storage facilities and uranium mines are established, drug trafficking is rampant, and welfare facilities are nearly nonexistent. Health problems are equally critical. The majority of Native Americans are exposed to diabetes and stress-induced high blood pressure. Moreover, drug abuse, alcoholism, and suicide rate are the highest among these peoples than in any other population group in the United States. Considering all of this, it should be no surprise that the average lifespan should be 48 for men and 52 for women on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation.

For these peoples, who have been bereft of their traditional ways of life, the annual “Future Generation Ride” is akin to a ritual of salvation. Indeed, many have overcome drug abuse or alcoholism through participation in this event, and the recovery rate amounts to 80%. During the long, 300-mile trip, they each grow a seed of hope in their hearts. Native American leaders explain that the “Future Generation Ride” is significant because it awakens in participants the value of their cultural identity. Perhaps for this reason, recent years have seen an increase in adults who take part in the event together with their children.

The “Future Generation Ride” is a natural outgrowth of the American Indian Movement, which arose in the 1970’s. Indeed, the movement signaled the first difficult but determined step in recovering Native Americans’ identity. These peoples declared freedom from oppression and sought political liberation, saying “no” to institutions and laws that had hitherto repressed them. Even though this called for a great deal of sacrifice, these peoples began to prepare their own future and to create an answer to the question “Who am I?” The “Future Generation Ride,” then, is an extension of this silent yet loud Native American Movement.

On my first visit to the snow-covered plains of Wounded Knee in the winter of 2003, I kept staring down at the ground, as if in search for traces of Chief Big Foot. The Native American friends who had accompanied me screamed and raged across the open country on horseback once they arrived. Now, I think I understand why they acted the way they did. In those plains, the dreams of a beautiful people are buried intact. In the world today, not only Native Americans but also small ethnic groups and countries precariously maintain their identities and lives in the face of a few superpowers and their interests. Even though the act of recording the history and lives of such minority communities most likely won’t save them from heartbreaking circumstances, records like this have important stories to tell. And the story in this book will bequeath to posterity a new truth and the lives of people who otherwise would be forgotten.

An expression frequently used by the Lakota, one of the Native American nations, “Mitacuye Oyasin” means “We are all related.” It expresses these people’s lives and philosophy, which respect nature, humans, and animals alike. Why, then, have they declined to such impoverishment today despite such beliefs? By taking part in the “Future Generation Ride,” which Native Americans hold to commemorate the souls of their ancestors and to recover their sovereignty and self-identity, I have looked back upon their sorrowful past and had a glimpse of their lives today. “Walking in Cold Water” is the Lakota name that Native American friends honored me with.

|

|